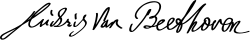

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1803, by Christian Hornemann

Portrait courtesy of timelines.com

12 December, 1810

Alas! Lament with me, my dear friends, for the great Beethoven is deaf! I have lost my entire sense of hearing . . . how, as a musician am I to go on living life? Fate has been cruel to me. Likewise, I shall be cruel to Fate itself! "I shall seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not bend and crush me completely!" I will live on. I will continue my life. I will live my life just as if I had not become deaf. I will be the world's greatest deaf composer.

I had first begun to notice something wrong with my ears as early as the year 1795. I could barely hear the harshest of noises, and the buzz in my ear was constant. Soft and low tones became unintelligible, and loud sounds became distorted. By 1801, I became completely deaf. In a few letters I wrote to my closest confidant, Karl Ameda, "How often I wish you were here, for your Beethoven is having a miserable life, at odds with nature and its Creator, abusing the latter for leaving his creatures vulnerable to the slightest accident ... My greatest faculty, my hearing, is greatly deteriorated." Ameda was most sympathetic towards me and my plight. But spilling out my most horrifying secret to one friend was not enough. I also wrote to Wegeler, saying "How can I, a musician, say to people "I am deaf!" I shall, if I can, defy this fate, even though there will be times when I shall be the unhappiest of God's creatures ... I live only in music ... frequently working on three or four pieces simultaneously." Whilst writing these letters, I comtemplated suicide . . . I thought about erasing the remnants of my life for being not able to hear was almost too much for me to bear. But I threw that thought away as soon as I had conjured it. For how could the world bear to lose their great Beethoven just because of something as simple as deafness? What horrors would the world face without my music? How could the world bear to go on without me? Thus, I decided to remain a living, and deaf, composer.

Perhaps God himself has sent me this deafness to challenge me. To see if I am worthy of being His musician. Well I am ready for this challenge. I will face it head on, and I will conquer it. My life has become a challenge worth fighting for, as I have written to Wegeler: "Free me of only half this affliction and I shall be a complete, mature man. You must think of me as being as happy as it is possible to be on this earth - not unhappy. No! I cannot endure it. I will seize Fate by the throat. It will not wholly conquer me! Oh, how beautiful it is to live - and live a thousand times over!"

Unable to keep all this grief and anger bottled up inside me, I penned out my feelings in my Heiligenstadt Testament on October 6, 1802. Here, I wrote "If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly I was flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing. Yet it was impossible for me to say to people, "Speak louder, shout, for I m deaf." Ah, how could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed --- Oh i cannot do it."

Although I wrote several pages of this Heiligenstadt Testament, I hid it and did not show a single soul what I had written. Only after my death, along with my will, will this paper be shown to and read by the world.

The Heiligenstadt Testament

Picture courtesy of timelines.com

Last page of Heiligenstadt Testament

Picture courtesy of lvbeethoven.com

Despite my illness, I continued to compose throughout my life until my death. One composition that I will never forget, is my Symphony No. 3, more commonly known as the Eroica Symphony. I had written this piece with Napolean as it's dedication in mind. Oh how excited I was to hear of Napolean's great accomplishments! I had thought he was a God-send, ready to revolutionize the whole of Europe! I had admired him to the point of worshipping him, only then did he disappoint me the most. After Napolean crowned himself emperor on December 2, 1804, I was so furious, my head so clouded with rage that I grabbed the nearest blade I could find and plunged it into my own manuscript: Sinfonie in E-Flat Major. Crossing out Napolean's name, I renamed my piece: composta per festiggiare il Souvenire di un grand'Uomo (composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.)

Oh but Napolean did not cease to disappoint me. As I finished working on my first opera, and also my last, the Leonore, (although my idiotic publishers renamed it Fidelio), Napolean stormed and took over Vienna. My beloved city of music! Thus, when my opera first played in Vienna, it's only audience were Napolean's French soldiers! Oh how angry I was! But nevertheless, my life continued and I forgot about Bonparte for a time.

In 1809, I would become the first independent composer ever! I had wanted to leave Vienna, although my patrons loved me too much to let me go, and were adamant upon my stay in the city. My old friend, Countess Anna Marie Erdody, Archbishop Rudolph, Prince Lobkowitz, and Prince Kinsky gave me a grant of 4,000 florins, so badly did they want me to stay! They must have loved my music very much. As I've said before, I've always known that nobles will bow before me.

I shall continue my life's story at a later date, for I am in the middle of composing my next symphony. Goodnight, my readers, although should you say goodnight to me back, I will not be able to hear it.

Sincerely,